The brilliance of Daum

From Daum Nancy, through post-war Daum crystal, to today’s exquisite pâte-de-verre creations, Daum has become a legend in glass.

But unlike other glass families such as Schneider or Legras, Daum’s founder, Jean Daum had zero experience of glass. In fact, he more or less fell into the business.

A solicitor by trade, he moved to Lorraine to stay French after Alsace was ceded to Germany in 1870. He made a business loan to a troubled local glassworks, the Verrerie Sainte-Catherine. When it became clear the factory was about to go bust, he saw two choices: take the hit… or buy the company and make a go of it himself.

In the footsteps of Gallé

Inevitably, the first few years were touch and go. The turning point came after Jean’s sons, Auguste and Antonin Daum (pictured, centre) threw themselves into the business. Auguste gradually got a handle on production costs.

Meanwhile, Antonin (1864-1930), an engineer by discipline, turned out to have a natural flair for design. He also had a towering model in Émile Gallé, then at the height of his fame after his glass ‘marquetry’ was acclaimed at the 1878 Paris Universal Exhibition.

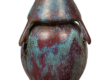

Over the next 20 years, Antonin Daum developed a huge catalogue of Art Nouveau designs, deploying ever more complex techniques. These included multi-layer cameo vases, enamel landscapes and applied glass embellishments in the shape of scarabs or dragonflies.

Over the next 20 years, Antonin Daum developed a huge catalogue of Art Nouveau designs, deploying ever more complex techniques. These included multi-layer cameo vases, enamel landscapes and applied glass embellishments in the shape of scarabs or dragonflies.

Pâte-de-verre sculpture also entered the inventory, using lost wax moulding methods, perfected by Amalric Walter at Daum.

Pâte-de-verre sculpture also entered the inventory, using lost wax moulding methods, perfected by Amalric Walter at Daum.

Success was crowned in 1900, when Daum and Gallé shared the Grand Prix at the Paris Universal Exhibition.

Daum and the École de Nancy

Antonin Daum was a founder member of the École de Nancy, the arts and crafts group led by Émile Gallé.

Inseparable from the Art Nouveau movement, it resulted in what a friend of mine calls ‘bondage glass’ 😉, blown glass with wrought iron courtesy of Louis Majorelle.

The berluze – a vase with rounded belly and a long, slender neck – was also a Daum speciality. The berluze came in all sizes, from miniature to monumental.

In the 1960s, the shape was revisited and given, literally, a modern ‘twist’.

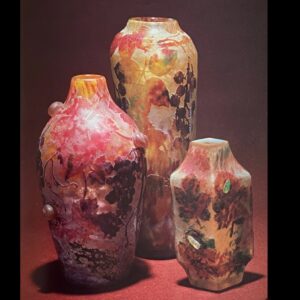

At the more affordable end of spectrum were Daum’s Art Nouveau ‘jade’ vases. They were in swirly powdered glass, with shapes that recalled a world of Japanese pottery.

Daum and Art Deco

In 1925, all eyes were on Paris and the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs. Out went the fluid, organic lines and complex hues of Art Nouveau. In came straight lines, sharp colours and contrasting surfaces.

For Daum, the Deco years were a time of expansion and diversification. The company experimented with alternative trademarks, such as ‘Lorrain’, ‘Moda’ or ‘Croismare’, the location of the newly acquired Belle-Étoile factory. There, he developed a new range of colourful, crystal heavy glass that spoke to modern tastes. To help seal its success, he recruited Pierre d’Avesn as designer.

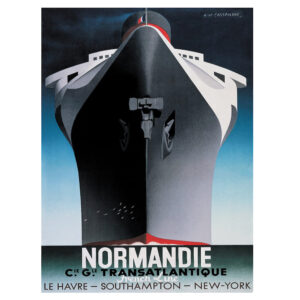

The high point of the decade came in 1935 with a contract for 9,000 items of glass and crystal for the luxury transatlantic liner, SS Normandie.

However, it was the swan-song for the Croismare works, earmarked for closure since the Great Depression.

Daum France, a transparent success

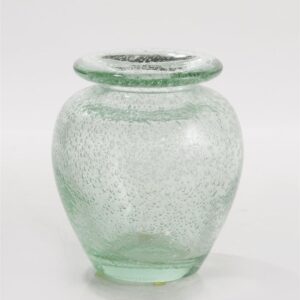

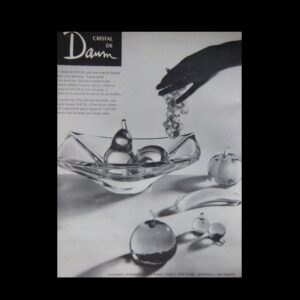

The 1950s brought opportunities and a major headache – a shortage of colour pigments. Michel Daum, Auguste’s grandson, responded by shifting production to clear, sparkling crystal with an extra high lead content. New era – new name. ‘Daum Nancy’ was replaced by ‘Daum France’.

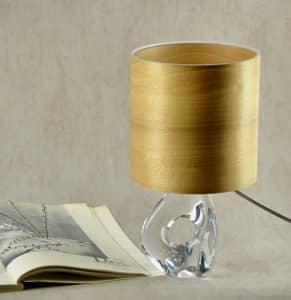

Lamps and bowls were pulled, stretched and coaxed into voluptuous abstract shapes that looked immaculate in minimalist homes (actually, they still do!) The more avant-garde pieces appeared in chic magazines, photographed to perfection by Pierre Jahan.

Meanwhile, Daum crystal tableware – glasses, carafes, knife rests and so on – was on every smart homemaker’s wishlist.

From crystal to pâte-de-cristal

Jacques Daum took over in the 1960s, the last in the family to do so. He boosted Daum’s prestige by partnering with famous artists, starting with Salvador Dali and César.

Daum brutalist designs of the late ’60s and ’70s feel as sharp and modern now as it did in 1969.

However, Jacques Daum’s most significant move was to return to pâte-de-verre, that special process pioneered by Amalric Walter over half a century earlier. This incredibly labour-intensive art involves lost-wax moulding and vitrifying coarse grains of 30% lead crystal at a heat of 900℃ for up to 20 days.

Daum is so highly specialised in this art, its savoir-faire is unrivalled anywhere in the world… a French legend. The solicitor from Alsace would have been proud.