Jean Painlevé jewellery : of seahorses and cinema

Wear a piece of Jean Painlevé bakelite jewellery, and you’re not just wearing Art Deco, but also a slice of cinema history. Because Jean Painlevé (1902-1989) is best known as a filmmaker, who blended science and art to pioneer a new genre: the nature documentary.

Jean Painlevé, the scientist

The son of Paul Painlevé, a mathematician and senior statesman, Jean Painlevé graduated from the Sorbonne in physics, chemistry and biology. With a promising academic career ahead of him, the world was his oyster.

But Painlevé had his own ideas.From 1925, he began taking a serious interest in cinema. As a biologist, he was convinced of the potential of film to bring the beauty and wonder of science to a wider audience.

His early films earned the admiration of surrealist figures such as André Breton and Man Ray. But, strange as it seems today, they scandalised the scientific establishment. Science, you see, was far too noble for the medium of Charlie Chaplin!

Jean Painlevé and l’Hippocampe

Painlevé’s breakthrough came in 1935, with his film, L’Hippocampe (The Seahorse).

The documentary follows a seahorse couple as they share parenting. In an astonishing role reversal, it shows the male seahorse releasing the babies from his pouch, as though he is actually giving birth.

The research was serious and original. As for the film, well, it was a sensation.

Which brings us to the jewellery, one of the earliest examples of film merchandising…

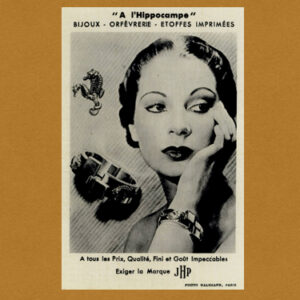

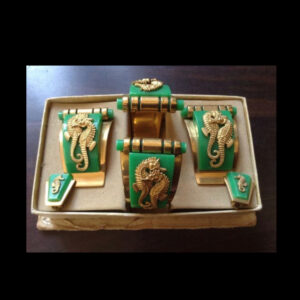

Riding the wave of success, in 1936, Painlevé and his wife, Ginette commissioned a range of seahorse accessories under the label JHP (H as in Hippocampe). One thing led to another; a boutique in Paris’s rue de Braque, another near the place de l’Opera.

Painlevé jewellery

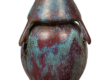

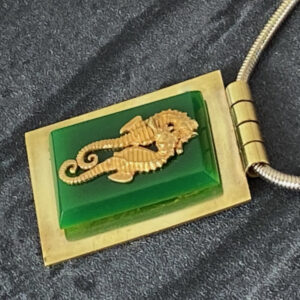

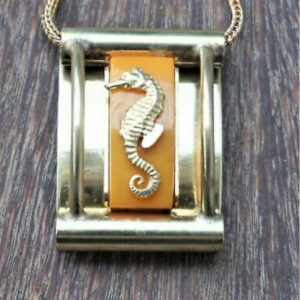

Painlevé Art Deco jewellery was manufactured to an extremely high standard. The coloured plaques are made of galalith or bakelite, topped with an animal motif, screw-mounted on a brass setting. Examples include pendants, necklaces, bracelets, bangles, dress clips and earrings.

As time went on, the Painlevés added new motifs, such as the salamander (lizard) and a mythical creature, the griffin. But it was the seahorse – Painlevé’s “living aquatic sculpture” – that most captured popular imagination.

After L’Hippocampe

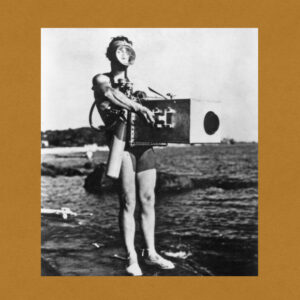

Naturally, the story of this brilliant and likeable man doesn’t end there. During the war, he took part in the French Resistance and was a marked man. He escaped to safety in Spain, where he continued to film and dive, using scuba kit he’d developed himself.

Painlevé made over 200 films, paving the way for the kind of thought-provoking nature documentaries we enjoy watching today. However, his most famous film wasn’t a nature documentary in the pure sense. Part documentary, part manifesto against Nazi appeasement, The Vampire (1939) follows the Brazilian vampire bat as it closes in for the kill. Warning: not for the squeamish!