Jean de Lespinasse pottery, from ‘industrial’ to desirable

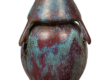

There’s something very modern about Jean de Lespinasse ceramics. Clean, sober lines and intense colours. Uncluttered, linear motifs. Size is also a factor, since the studio often made the kind of big, standalone pieces that exude presence wherever they go

Today, Jean de Lespinasse pottery is sought after by private collectors and interior designers – quite the turnround for a discreet mid century studio dismissed in its day as ‘industrial’.

De Lespinasse, the early years

Soon after World War II, Jean de Lespinasse and his wife, Simone, opened a craft business in Nice making candles. De Lespinasse was then in his forties; the couple are believed to have met in the Resistance. Someone suggested they make candle holders, and it was probably that casual remark that led them to pottery.

Initially, they bought pottery blanks and decorated them. Early freeform vases were boldly striped in yellow and black. However, one thing led to another, and by the mid-1950s, the studio was turning its own pottery and forging its own style.

A family affair

Like many a post-war French businesses, the studio was run on family lines. Jean Saguès, Simone’s son by a previous marriage, turned the pottery for the moulds. When it came to removing and finishing the large plaster casts, it was a case of all hands to the wheel.

Sylvie Fournier, the couple’s daughter-in-law, applied her talent and and art training to the decor, particularly the sgraffito motifs, which were hand etched with a nail.

Employing around a dozen people at its height, the studio was low-profile and businesslike. It traded under the unassuming name of SOCFRA (a contraction of “Société Française”). Jean de Lespinasse had no dedicated shop. Each year, the studio showed its wares at trade and decorative arts fairs in Lyon and Paris. Order books filled up, and wooden crates packed with pottery were dispatched to customers in Corsica or by train to all corners of France. Sometimes, hotels would commission special friezes or decor. And from May to October, the public could buy direct from shops rented in Saint Paul de Vence, Saint Maxime and, for a brief spell, Vallauris.

Jean de Lespinasse and Vallauris

The shop in Vallauris was an experiment that lasted only two seasons, but that brief presence explains why Jean de Lespinasse is sometimes mentioned as a “Vallauris” potter.

However, he didn’t move in the same circles as Roger Capron, Jean Derval, Robert Picault or the other famous designers associated with the ceramics revival there. Quite the opposite, in fact. In the de facto hierarchy of the day, Jean de Lespinasse was regarded as a manufacturer, rather than a “créateur”. How ironic, then, that some of these ‘industrial’ pieces have become design classics.

The de Lespinasse look

Today, a range of freeform pieces from the 1950s are among the most sought-after items. Sassy in black with incised decor, they reveal flashes of primary red or yellow inside.

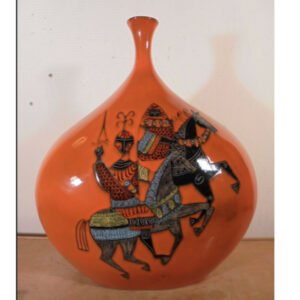

In the 1960s, the studio gave more free rein to colour, with bright gloss reds or oranges, some etched in an all over fish-cale effect.

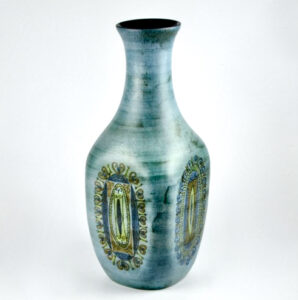

Semi-matte pieces came in graded bands of earthy brown, muted grey or cool, Mediterranean blue.

The polychrome decor, where there was any, could be abstract or figurative – dark-eyed girls, fantastic beasts, ancient warriors with sgraffito chain mail. Often, it was confined to just one striking motif.

In its 30-year existence, Jean de Lespinasse created somewhere in the region of 300 original models, excluding variations. For a small studio, that meant short runs and a relatively low volume of production. The result? A demand that keeps growing, and a large pool of desirable pieces… but first you have to find them!