Charles Schneider glass – modern luxury for the 20th century

In the 1970s, you could pick up sublime Charles Schneider glass for a song in the fleamarkets of Paris.

But that was then, when collectors had eyes only for Gallé and Lalique.

Nowadays, Charles Schneider’s reputation has been restored, as one of the most innovative French glassmakers of the 20th century.

A child of the École de Nancy

Charles Schneider grew up in the dynamic atmosphere of the École de Nancy, whose founder members included Antonin Daum.

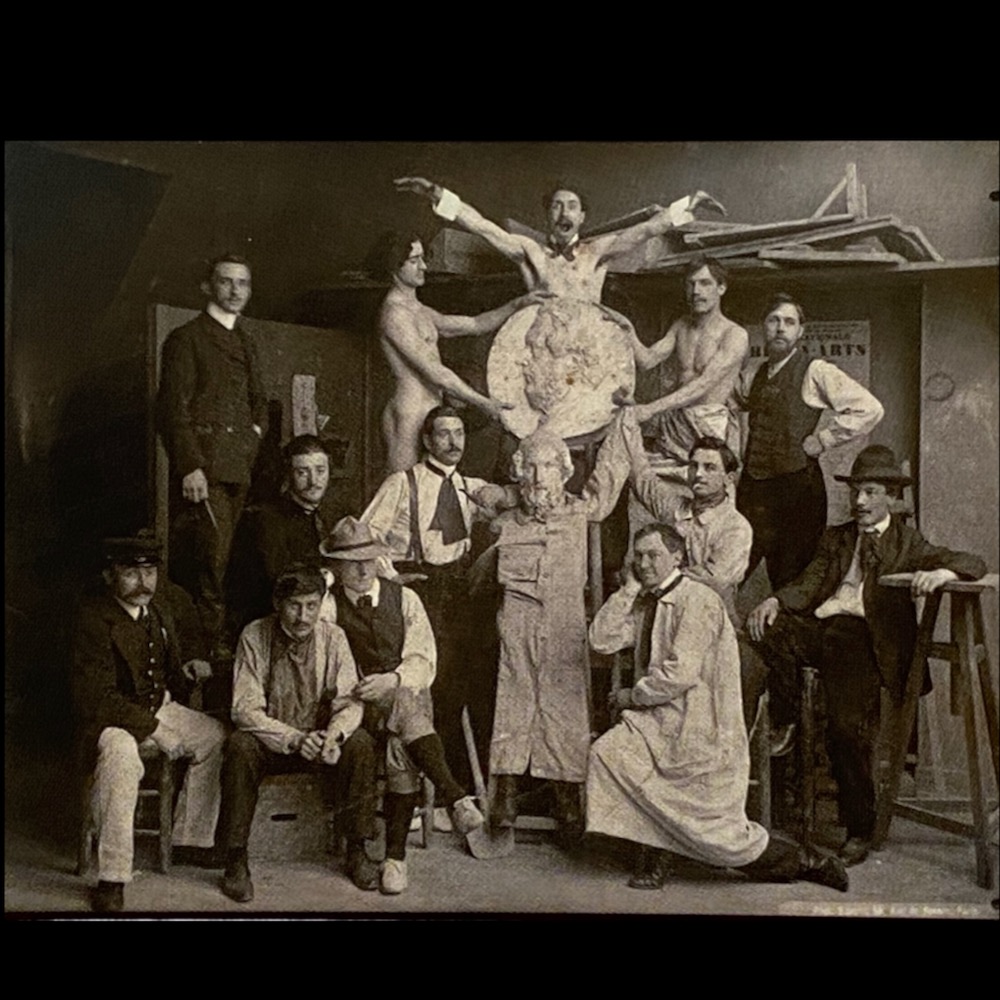

Aged 16, he was taken on to train in Maison Daum’s in-house school. He quickly stood out for his art talent, so much so that Daum sponsored him to study at prestigious Paris Beaux Arts.

Apparently, he flourished there, if this 1905 photograph of him and his classmates is anything to go by!

The Schneider glassworks

The arrival of Paul Daum brought sweeping changes to the Daum factory. Ernest, Charles’ elder brother, who worked in the sales department, was the first to lose his job. In 1913, Charles, too, was laid off. The brothers decided the moment had come to start their own glassworks, the Verreries Schneider.

Using Ernest’s golden handshake, they bought a disused glass factory in Épinay-sur-Seine. With Charles’ imagination and Ernest’s business acumen, what could possibly stop them… apart from WW1? The brothers were called up in 1914, then discharged to start producing medical glass for the war effort.

But by 1920, the factory was doing what it set out to do: making art glass from original designs by Charles Schneider.

Success came quickly.

True to the spirit of Gallé

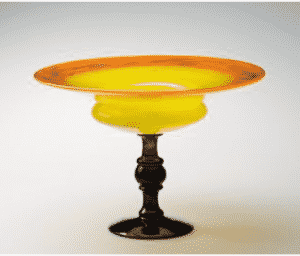

Schneider’s early designs emulated Émile Gallé, with naturalistic, Art Nouveau motifs wheel-engraved in cameo glass. But he also forged a distinct Schneider style. An example is the miniature Bijou series, influenced by Venetian art glass, with purple-black or latticino glass stems.

Schneider drew on a palette of around 50 colours, harnessing them in subtle, powdery combinations, or in strong contrasts using overlays.

Schneider at the forefront of Art Deco

Schneider glass sold in high end boutiques such as Primavera and La Maîtrise, as well as from the company’s two showrooms on the Paris’s famous Rue de Paradis.

Come the 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Deco, and orders began to roll in from America. The factory had to be expanded to accommodate the 500 glass workers needed to keep pace with demand.

Charles Schneider not only grasped the new Art Deco style, he helped shape it. An incredibly prolific designer, he often stayed up all night to sketch new models.

As the decade wore on, lines became purer and decors more geometric.New effects included a granular, acid-etched texture known as criblé. Some pieces featured stretched bubbles that make the glass seem quite ethereal. Even today, they still look strikingly modern.

Schneider glass signatures

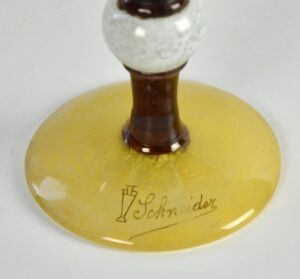

The company used three trademarks: Schneider, Le Verre Français and Charder (a contraction of Charles Schneider).

Glass with the Schneider signature tends to be more subdued in style. It reflected French taste, which was relatively conservative.

Le Verre Français and Charder designs were more exuberant and, more often than not, cost more to make. These ranges were popular in the US, Brazil and Argentina.

Early Verre Français pieces are sometimes accompanied by a tiny red, white and blue berlingot, embedded in the glass.

Verreries Schneider vs Degué

Schneider glass was a true expression of the Roaring Twenties, and it dominated the glass scene for well over a decade. But then came the Wall Street Crash, and a crippling legal battle with David Guéron, the owner of the Degué glassworks.

The Schneider brothers accused the company of flagrantly plagiarising its designs. In the end, they won the case, but by then the Depression had already taken its toll.

The Schneider glassworks, a byword for luxury and modernity for almost 15 years, filed for bankruptcy in 1939.

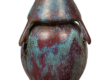

Cristallerie Schneider, a post-war renaissance

Of course, the story doesn’t end there. In 1949, with the help of his father, Charles Schneider Junior and his brother Robert-Henri, founded the Cristallerie Schneider in Épinay-sur-Seine. They restored the modernity of the Schneider name throughout the 1950s and ’60s.

Robert-Henri, a sculptor by training, was the creative force behind the venture. The young company produced sculptural crystal lamps, bookends and centrepieces pieces in lead crystal, signed with a etched signature in script . The shapes were avant garde, sometimes embellished with tiny, controlled bubbles.

Cristallerie Schneider was a worthy rival to Daum France and the pieces vie with Daum in style and quality. A factory fire and the oil crisis led to the decline of the Cristallerie Schneider. The factory closed in 1981.

Disregarded until recently, Cristallerie Schneider pieces are now finding favour with a younger generation of design lovers, combing the fleamarkets of Paris …